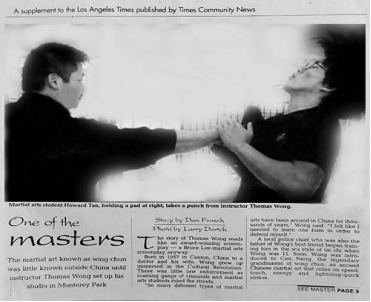

One of the Masters

Dan Frosch

The story of Thomas Wong reads like an award-winning screenplay - a Bruce Lee martial arts screenplay, anyway.

Born in 1957 in Canton, China to a doctor and his wife, Wong grew up immersed in the Cultural Revolution. There was little law enforcement as roaming gangs of criminals and martial arts students ruled the streets. So many different types of martial arts have been around in China for thousands of years," Wong said. "I felt like I needed to learn one form in order to defend myself."

A local police chief who was also the father of Wong's best friend began training him in the Wu style of Tai Chi when Wong was 11. Soon, Wong was introduced to Sum Neng, the legendary grandmaster of Wing Chun, an ancient Chinese martial art that relies on speed, touch, energy and lightning-quick strikes. Impressed by Wong's unusual ability to match the moves of the grandmaster, as the story goes, Neng took young Wong into his tutelage and began private, personalized training. Soon, it is said, Wong was successfully using his Wing Chun techniques to fend off attackers - "often as many as 10 at a time" (eat your heart out, Bruce Lee) - with a combination of speed and agility that when Wong demonstrates it even now, is awfully impressive.

"The advantage of Wing Chun," Wong said, "is that it does not telegraph what one is going to do to his opponent like almost every other form of martial art. When an opponent tries to strike me, I can feel their energy at first contact - Wing Chun allows me to use my own energy and counter instantaneously." Wong was able to stun opponents and attackers alike with his newly acquired skill, he admits.

Through Neng, Wong was also able to study under some of China's legendary martial arts masters in other disciplines like DeSui (ground fighting) and Chi-Gung, and became skilled in those forms of martial arts as well.

Wong recounts how rival groups of martial arts students would challenge him and his Wing Chun colleagues to fights to see whose martial art was more potent. "The fights were quick and dangerous - whoever was left standing was the winner," he said. Wong has knife marks on his forearms to prove it. "The only way to truly perfect your martial art is to test it in combat," he said.

Wong came to Southern California in 1974 and settled in Monterey Park with his family when they came to visit his ill grandfather. He began taking classes at Cal Poly Pomona and at Pasadena City College. He also began teaching Wing Chun to small groups of college students who were eager to learn a form of martial arts that was previously unknown in the United States.

As the word would get out on Wing Chun, Wong recalls his martial arts skills being challenged again. One of Wong's current students, Sid Cooke, repeats his tale: "Sifu (a respectful term for a master of kung fu) was once challenged by a 6-foot-4 wrestler in front of a crowd of people he was teaching. Sifu took him to the ground in a matter of seconds." Cook immodestly attests to Wong's modesty. "Sifu has fought thousands of fights - real fights in China; people in this country hear about him and his legendary status and want to challenge him."

For his part, Wong is content to stay out of the spotlight. "Most times when people challenge me, I can tell if they are experienced in a martial art or not just by observing the manner in which they are acting," he said. "I don't like to fight many of them, because I really don't want to hurt anyone - Wing Chun is so powerful, it must be used with extreme caution." In fact Wong is so humble that he seems almost reluctant to show off his ability. He once turned down an offer by Jerry Poteet, one of Bruce Lee's best-known disciples, to write a book on the teachings of Wing Chun. But then the grandmasters of Wing Chun called him from China and asked him to introduce Wing Chun to America. Wong agreed and now holds small classes in his backyard garden. Wong seems most content in the tranquility of his own home.

"At this point, I'm ready to pass on my art to others," he said.

-

For information on Wing Chun training, call (626) 571-8787.

-

This article was written by Dan Frosch, a news reporter and contributor and first appeared in the San Gabriel Valley Weekly, a supplement to the Los Angeles Times, published by Times Community News for the week of September 17-23, 1999.